I delivered this as a flashtalk during my 1st Automattic Grand Meetup. It was in Whistler, Canada (September 2017).

Most people are familiar with spreadsheets applications, but there was a time where they didn’t exist. We had to resort to other means to keep track of numbers — for example, ledgers.

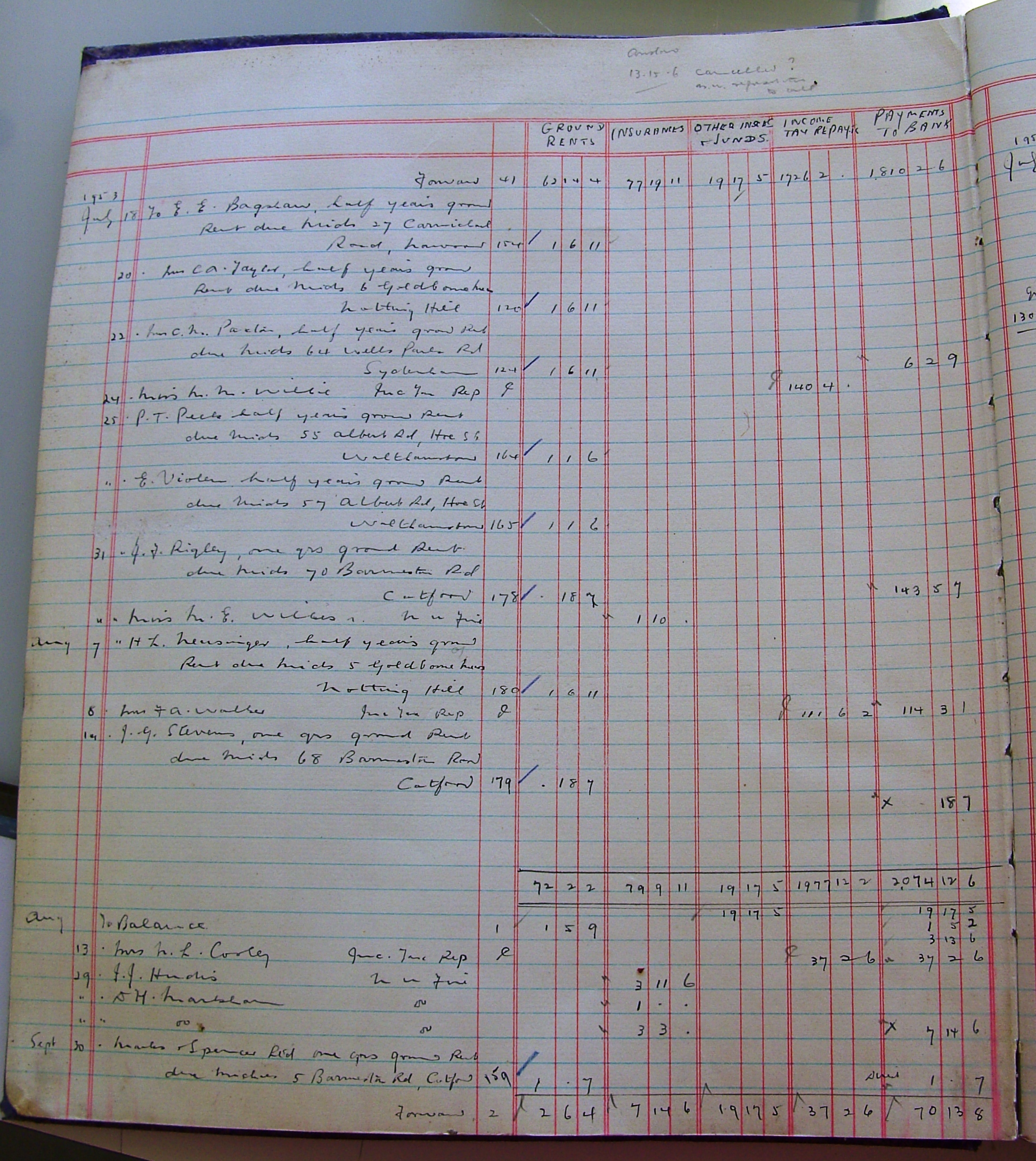

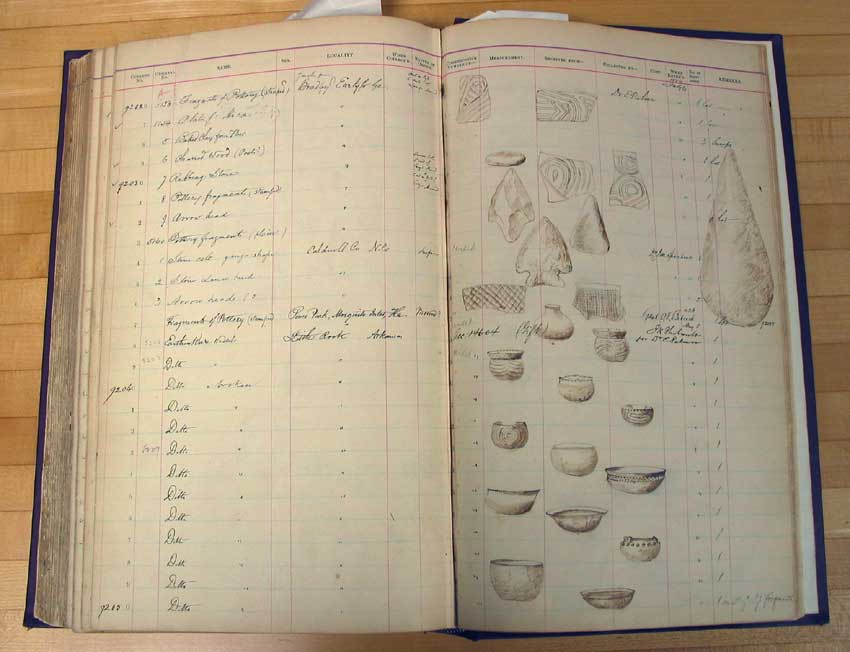

A ledger is an actual book used to track inventories of material, credits, etc. Ledgers being books, they have pages, aka sheets. If you open any paper book by a given page, you’ll see two of them at once because pages, or sheets, are spread. So you are looking at spread sheets — that’s how the name came to be.

Keeping track of numbers has been useful since the dawn of humanity. During the first decades of the XX century, building census (how many are we?) and ballistic experiments (how effective are we at hitting the target?) were problems many states threw technology at, and so technology for calculation progressed.

By the end of the 50s, specialized machines for calculation were in the market. The IBM 632 was one of them and was prized at $6.000 — 100% of an USA family’s income at the time. These machines weren’t affordable to many. All they could do was printing predefined templates: given some input numbers they’d produce canned reports. There was no interactivity built-in and they took some training to operate.

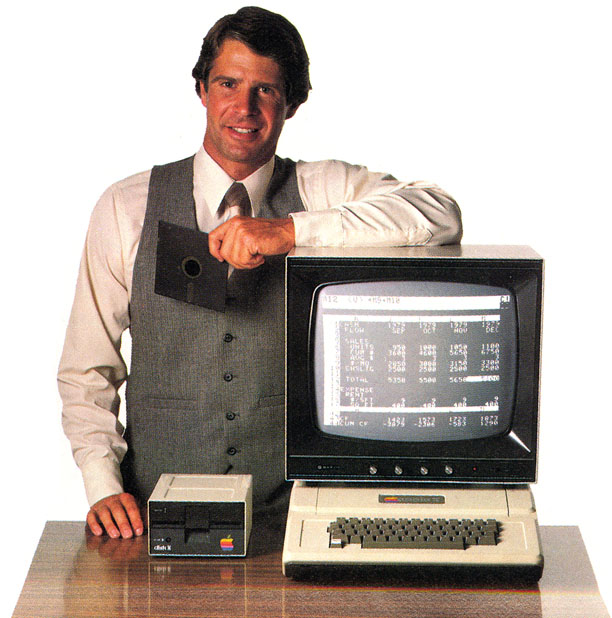

But progress continued and, a couple of decades later, those specialized machines had evolved into general-purpose ones: computers. Released in 1979, the Apple II was one of the most popular. It costed about $1 300 — ~8% of an USA family’s income at the time. At that price point, it was something some families and little business could afford. But what would anyone buy a computer for? To keep track of numbers, of course.

If you bought an Apple II, you could use the first spreadsheet application we know as such: VisiCalc. At $100, VisiCalc is considered the first killer application of the history of computing. The reason is that VisiCalc was the main driver of Apple II sales: people bought a $1 300 machine to being able to use a $100 application.

VisiCalc defined what a spreadsheet was going to be: an application that lets you introduce some numbers and outputs a different set of them, interactively — the output would be recalculated every time you changed the input. The concept of an interactive spreadsheet is ubiquitous today, but it was popularized by VisiCalc.

Once the concept was stablished, the evolution of spreadsheets was about iteration and adaptation. We found ways to make it faster, add some more features, and port it to newer distribution platforms as they emerged (Windows, Linux, the web, etc.). It’s 2025, and we’re still using the same concepts introduced by VisiCalc in 1979. The core aspects of a spreadsheet haven’t changed, but VisiCalc is no longer popular.

A lot of what happens in software is that way: once you get the right concept, it doesn’t change much. Concepts are the real win.

Thanks for staying until the end, and remember: if you do spreadsheets, you’ll excel at work.

Leave a Reply